Watching the commemorations at Thiepval for the Battle of the Somme which began 100 years ago today I was filled with nostalgia for a lost age: 22nd June 2016 – the day before my country voted to leave the European Union.

I am familiar with this, and other, First World War cemeteries from several school trips to the battlefields. My students read extracts from poems, plays and novels at the exact locations in France and Belgium where the terrifying violent events took place. This extract from The War Graves by Northern Irish poet Michael Longley is an example of what we read at Thiepval.

The headstones wipe out the horizon like a blizzard

And we can see no farther than the day they died,

As though all of them died together on the same day

And the war was that single momentous explosion.

Today, however, it was the great and the good who read extracts. Shivering, rain-showered school children from France, Britain and Ireland, merely laid wreaths on each individual grave in the serried ranks of simple, fanned out stones.

As the bugler played the Last Post tears issued from my eyes in concert with drops of rain squeezed from the lowering grey skies overhead. The skies seemed to weep for the foolishness of those who promote nationalism above friendship and communal endeavour. Those in power in both 1916 and 2016 are careless of those who are vulnerable.

Today our outgoing Prime Minister, David Cameron, sat and stood shoulder to shoulder with the presidents of France and Ireland; a position which must have seemed ironic to others as well as me.

Huw Edward’s, dignified and grave commentary did not, however, deal with this irony. But it seemed obvious from Cameron’s shamed face and stance that he was grieving, not only for the millions of dead soldiers but for his own cowardly and destructive decision to call a referendum – mainly it seems to defeat Nigel Farage, who is not even a member of parliament, and whose disgusting party UKIP has only one representative in the House of Commons.

Simultaneously, back in London, having stabbed his erstwhile colleague, Boris Johnson, in the back, Michael Gove, a former education secretary (who was so hated by teachers that Cameron had remove him from his post)  attempted to bribe Conservative voters, with promises of money for the NHS, in his efforts to become an unelected prime minister. I am ashamed of my country and its farcical leaders and, it is almost with glee that I watch them, across all political parties, self-destruct. I am proud to be living in Ireland where the flag of the European Union still flies beside the trídhathach na hÉireann. Not to say that the Irish have never been guilty of what Tisdall (see below) describes as ‘aggressively chauvinistic nationalism’.

attempted to bribe Conservative voters, with promises of money for the NHS, in his efforts to become an unelected prime minister. I am ashamed of my country and its farcical leaders and, it is almost with glee that I watch them, across all political parties, self-destruct. I am proud to be living in Ireland where the flag of the European Union still flies beside the trídhathach na hÉireann. Not to say that the Irish have never been guilty of what Tisdall (see below) describes as ‘aggressively chauvinistic nationalism’.

I am filled with gloom and dread when I think of the future of my country and what may happen to the younger generation for whom, amongst other generations, the soldiers of the First World War fought. In the Guardian Simon Tisdall paints a sorry picture of ‘England’s inexorable decline‘.

I am terrified by the current wave of racist attacks and slurs and by what may happen when those who voted to leave the EU find out that there is still a shortage of ‘proper’ jobs and reasonable housing. I am terrified of what will happen when the cash-starved NHS cannot bring ex-pat nurses and doctors to heal the sick. And I am terrified that when I am truly old there will be no kind Eastern European, South East Asian and African carers to watch over my failing body and mind.

As is so often the case I turn to W.B. Yeats for the necessary words:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Still, I’d like to be optimistic like Jeanette Winterson who wrote in the Guardian about a new story for England and a new party for the left. I’m with her. Three cheers for the Equality Party.

Works cited

Longley, M. The War Graves

Sassoon, S. Aftermath

Yeats, W. B. The Second Coming

Like the final stanza of that poem, the pages of the book are filled with references to oriental gold. Ironically, for lovers of Yeats’s poem, Brotton tells of a gift, from Queen Elizabeth I to Sultan Murad III, not the other way around, of a clockwork organ which was played, in 1599, to entertain ‘the lords and ladies of Byzantium’ in the same palace that Yeats chose for his golden mechanical bird. The Sultan was not ‘drowsy’ but delighted, and offered the organ-maker, Thomas Dallam, his choice of the palace concubines. It seems that Dallam merely accepted a bag of gold.

Like the final stanza of that poem, the pages of the book are filled with references to oriental gold. Ironically, for lovers of Yeats’s poem, Brotton tells of a gift, from Queen Elizabeth I to Sultan Murad III, not the other way around, of a clockwork organ which was played, in 1599, to entertain ‘the lords and ladies of Byzantium’ in the same palace that Yeats chose for his golden mechanical bird. The Sultan was not ‘drowsy’ but delighted, and offered the organ-maker, Thomas Dallam, his choice of the palace concubines. It seems that Dallam merely accepted a bag of gold.

rage

rage

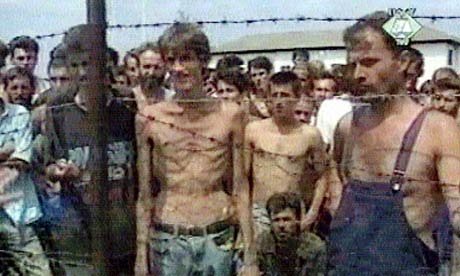

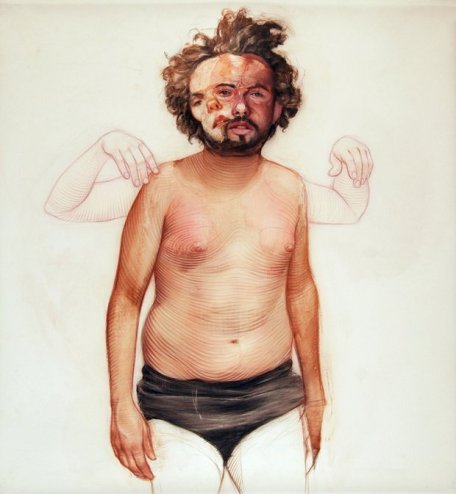

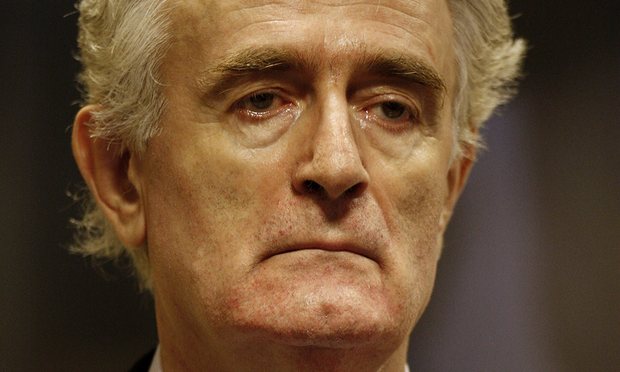

In the novel O’Brien imagines that a character, Vlad Dragan, similar to Karadžić, ends up in a small town in Ireland. The inhabitants seeing a face like the one at the top of this page, analyse it, as one might, as dignified and compassionate. The novel deals with many things, but the images that stick in one’s head are the ones involving Fidelma, the heroine, and Vlad. Fidelma, childless and unhappily married, falls in love with, and becomes pregnant by, the newcomer. Then, in a brutal scene, the baby miscarries as she is beaten by former associates of her lover. Fidelma travels to Holland to attend the trial and requests a visit with Vlad. There is also a dream sequence in which she meets him in the “conjugal room”. O’Brien is fascinated by the seductive power of evil and stated in an

In the novel O’Brien imagines that a character, Vlad Dragan, similar to Karadžić, ends up in a small town in Ireland. The inhabitants seeing a face like the one at the top of this page, analyse it, as one might, as dignified and compassionate. The novel deals with many things, but the images that stick in one’s head are the ones involving Fidelma, the heroine, and Vlad. Fidelma, childless and unhappily married, falls in love with, and becomes pregnant by, the newcomer. Then, in a brutal scene, the baby miscarries as she is beaten by former associates of her lover. Fidelma travels to Holland to attend the trial and requests a visit with Vlad. There is also a dream sequence in which she meets him in the “conjugal room”. O’Brien is fascinated by the seductive power of evil and stated in an