I have read the story for the first time – having only just heard of it! The tale is a familiar one: the execution of Englishmen by Irishmen, in reprisal for English executions of Irish. But there is something different about the way in which this story is written. This blog is about what I noticed in the story but, as I have not read any criticism, I may just be repeating what everyone else has said.

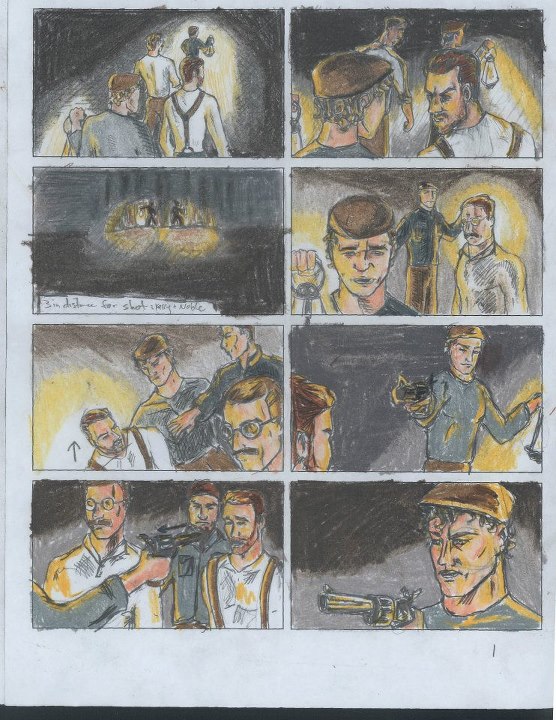

The setting of Guests Of The Nation is clearly of central importance and there is a visual element about it which has led amateur and professional filmmakers, as well as theatre groups, to adapt it. And its place in the genre of Irish Literature is assured by its stereotypical location – a cottage by a bog. But I am writing only of O’Connor’s use of language.

Note first that the title of the story, unlike that of the short film, incorporates the definite article, ‘The’ rather than the indefinite article ‘A’. So Ireland is not a nation; she is the nation. And this, it seems to me, illustrates a struggle that Ireland and Irish writers have engaged in, not only since 1916, and not only since 1926, but for many centuries. Edward Spenser in A View of the State of Ireland (1596) presented an analysis of Ireland and Irishness, but this was a patronising, patrician, and, of course, English view.

How then is it possible for Ireland to establish herself as herself, rather than, what Edward Said terms ‘The Other’? Even now, in 2016, the island of Ireland is still divided, preventing her from becoming, as Donne said, ‘an island entire of itself’. In using the definite article ‘The’ O’Connor is, as many Irish writers do, and have done, exploring the essence of his country and, perhaps, trying to contribute to the creation of Irishness.

In his ‘Nation’ O’Connor places some ‘Guests’ who are part of a occupying force. The word ‘Guests’ might, at first be seen as ironic as the English have over the centuries not been invited guests so much as resented imperialists. So what has O’Connor to say about this ‘Nation’ and these ‘Guests’? It is necessary, therefore, to see how he formulates the characters and motivations of the ‘Guests’.

This title, Guests Of The Nation, as titles often are, is key to understanding the text. But I think the dialogue is even more important in explaining O’Connor’s point. Something strange is afoot. Register. Cadence. Syntax. Accent. The formal register, is usually deployed by English or Anglo-Irish characters in Irish Literature, but in this story, on the whole, it resides in the mouths of the Irish characters. One such, Donovan, who is described as having an ‘uncommon broad accent’ speaks thus: ‘And what difference does it make? The enemy have our prisoners as long or longer, haven’t they?’ There is no attempt to mimic an accent and the syntax is formal. Donovan’s language is not recorded as regional. Nor does it identify him as ‘slow’ although the narrator, the oddly named, Bonaparte, defines him as such.

On the other hand, one English character, Hawkins, is almost more Irish than the Irish. He knows ‘the countryside as well as we did and something more’. Hawkins has also learnt to dance Irish dances, such as ‘The Walls of Limerick’ and ‘The Siege of Ennis” although he could not teach English dances to the Irish as ‘our lads at that time did not dance foreign dances on principle’. O’Connor gives Hawkins a kind of Cockney ‘brogue’: ‘Mary Brigid Ho’Connell was asking abaout you and said ‘ow you’d a pair of socks belonging to ‘er young brother’. The alternative spelling of ‘about’ seems to be O’Connor’s attempt to locate Hawkins’s language in a particular location and a particular class. Additionally Hawkins loses the ‘H’ in his name, becoming, when addressed or described, ‘Awkins, but in his speech he adds unnecessary ‘H’s whilst aspirating those which should be pronounced. ‘And you believe that God created Hadam and Hadam created Shem and Shem created Jehoshophat? You believe all the silly hold fairy-tale about Heve and Heden and the happle?’

Clearly O’Connor is deploying humour here, as he does when he names the other Englishman Belcher, in spite of the fact that this character is generally silent. When he does speak, Belcher invariably uses the word “chum”. This word is slang, emanating from the upperclass English students of the University of Oxford, and means a friend.

Whether Belcher intended it or not his Irish guards choose to adopt both the word and the sentiment. They become ‘chums’ of their English ‘Guests’. At the point when the imminent execution is revealed Hawkins protests ‘Me and Bonaparte are chums’ receiving the reply from Bonaparte, who will take part in the killing, ‘I mean it, chum’. There follows a heated discussion between the ‘chums’ opposing two ideas, that of ‘duty’ to a brigade or a country to that of being ‘chums’ and sticking together. Bonaparte seems to agree with his ‘chums’ that the fellowship between men is more central to the human condition than any idea of ‘duty’. Nevertheless he is complicit and active in the shooting of his ‘Guests’. He is sticking to the principle that prevents the Irish from dancing English dances. And also to the principle of saving his own life in the face of ‘men on the Brigade you daren’t let nor hinder without a gun in you hand’.

But it is O’Connor’s use of the oh-so-English word ‘chum’ that strikes me as central to an understanding of the story. Despite the backstory of this execution being in retaliation, O’Connor positions the Irish characters as oppressors; in cold blood they kill their ‘chums’ and sink them ‘in the windy bog’. The Englishness of the word ‘chum’, a word which Bonaparte states ‘lingers painfully in my memory’, permeates the text throughout and suggests the power of the English nation, and her insistence that, even when it is a bog, ‘there’s some corner of a foreign field/That is forever England’. It’s as if O’Connor is portraying Ireland as still ‘The Other’, as still unable to eschew that which is English. The most senior Irish officer, Donovan, says, ‘Why the hell should your people take out four prisoners and shoot them in cold blood upon a barrack square?’ His idiom is English. Through dialogue O’Connor subtly and covertly acknowledges that the power of England, English and Englishness is still overwhelming any attempt to create Ireland as entire to herself.

Works cited

Brooke, R. The Soldier Gloucester: New Numbers Magazine January 1915. Print.

Donne, J. Donne’s Devotions (1624) Cambridge University Press. 1923. Print.

O’Connor, F. Guests Of The Nation. London: Macmillan. 1931. Print.

Said, E. Orientalism. London: Penguin. 1977. Print.

Speers, D. Guests Of A Nation. Dir. Daniel Speers. SpearsSwift Productions. 2012. Film.